This foresight activity was part of the EU FP7 Blue Skies Project aimed at piloting, developing and testing in real situations a foresight methodology designed to bring together key stakeholders for the purpose of exploring the longer term challenges facing their sector and building a shared vision that could guide the development of the relevant European research and policy agenda. One of the four topics chosen in this project was future innovation policy in Europe, as an example of a cross-cutting policy area that affects different policy levels – from European to regional. The exercise was received with great interest by stakeholders and policy actors, leading to high-level participation from member states and at the EU-level.

Preparing European Innovation Policy for the Challenges of the Future

The Europe 2020 agenda has moved innovation to the centre stage of European policy. In the area of innovation, the EU aims to launch a flagship initiative entitled the Innovation Union, outlined in an EC communication in September 2010 (EC 2010).

Stepping up innovation performance is regarded as key for overcoming the current economic crisis, for increasing productivity and creating new markets. It requires improving Europe’s attractiveness for investments in research and innovation, which is hampered by the low efficiency and effectiveness of these investments, even though major differences exist across EU member states and regions. This is an issue of major concern in the light of the changing patterns of global competition, with new countries, such as BRICS, which are entering the stage and quickly strengthening their innovation potential.

At the same time, it is increasingly recognised that, apart from these immediate economic goals, a more long-term concern with the sustainable development of European societies has emerged to demand greater attention. We are confronted with a number of societal ‘Grand Challenges’, which require major innovative, often systemic solutions in order to be tackled successfully: climate change and food supply, scarcity of valuable resources (e.g. water, raw materials, biodiversity) and the changing age structure of our societies, social disparities and healthy living, education systems to meet the demands of the knowledge society, to mention just a few.

These two core drivers of innovation, i.e. the interest in overcoming the economic crisis and tackling the Grand Challenges, which are to be addressed through investments in research and innovation, point to a delicate balance to be struck between the benefits that an individual entrepreneur can expect from his or her investments and the societal costs and benefits from such investments and related spill-over effects. Future innovation policy needs to devise the right framework conditions to reconcile these two important but sometimes contradictory cost-benefit considerations and to do so against the background of changing patterns, practices and models of innovation.

The changing nature of and demands on innovation require rethinking the existing rationales for policy intervention in the light of the EU 2020 agenda. An incremental improvement and upgrading of conventional innovation policies will not do the job; current innovation policy is riddled with too many fundamental flaws and deficits. A major overhaul is needed of the governance structures and processes in the field of innovation policy. It is not only a question of what future innovation policy should look like but also how to move towards a new organisational model for innovation policy. It should enable a coherent policy approach and thus ensure that counterproductive effects of different policy areas are avoided and that innovation is paid due attention also in other policy areas than those directly devoted to research and innovation. Moreover, it is crucial to establish a transparent and coherent division of labour between regional, national and European policy levels as well as efficient cooperation between member states, for instance, on issues such as access to research funding or the engagement of national organisations across borders.

Success Scenario Approach

Based on a comprehensive background paper, a workshop was organised in Brussels on 27/28 May 2010 with about 30 high-ranking experts and decision-makers. It focused on identifying perceived gaps in innovation policy to be tackled to support Europe on its way towards an Innovation Union.

The purpose of the workshop was to bring together experts from different policy areas and levels of relevance to innovation in Europe with experts from research and industry to analyse the relationship between sectoral, cross-cutting and innovation policy agendas and their implementation at the European and national level, and to explore the means and actions for improving their coherence. A first step in the process was to develop a vision how European institutions can take shared responsibility for innovation and formulate requirements and key challenges for the future of innovation policy. A second session aimed at identifying key policies to support effective innovation, with an emphasis on the European policy level. The results were condensed into a success scenario framework for future European innovation policy. As a third step, the workshop focused on matters of innovation policy governance; an issue that has not received much attention in recent EU innovation policy debates. The time horizon of the exercise was 2020.

Apart from its contribution to current innovation policy debates, the exercise was also to pilot and test in real situations a foresight methodology designed to bring together key stakeholders to explore the longer term challenges that face their area. The methodology is inspired by the notion of success scenario. The purpose of such a scenario is to set a ‘stretch target’ for all the stakeholders. In this specific case it aims to build a shared vision capable of guiding the development of the relevant European research and innovation policy agenda. This includes anticipating changes of the European research and innovation landscape, of national and European policies and of associated governance mechanisms, which would be needed to take forward that agenda.

Gearing Innovation Policy toward Grand Challenges

The combination of interactive success scenario development and desk-based innovation ecosystem mapping brought up a number of important findings. Three of them merit particular attention:

A Broader Understanding of Innovation

The workshop underlined that future innovation policy will have to be based on a much broader understanding of innovation than at present. Four main features will have to receive much greater attention than today:

- Innovation takes place in an ecology of different actors and activities, comprising research, market and societal demands, finance, and institutional frameworks, i.e. it is based on a network of relationships between innovation actors and the environment structuring those relationships. The ability to source knowledge developed elsewhere or to be a knowledge supplier, as captured in the terminology of ‘open innovation’, has started to transform business models and processes. This development has led to an embedding of local knowledge production in global innovation networks, but it is also recognised that the local context still matters for providing appropriate solutions.

- Users have a prominent role to play in devising innovations that are in line with specific and local requirements. Greater concern for the needs and interests of users is reflected in the growing recognition of the importance of innovation in services. While representing around 70% of GDP in most European countries, services have long been neglected by innovation policy. The public sector plays a much more important role for innovation than has been recognised in the past, as a user and shaper of innovation as well as by stimulating the capabilities of potential users to specify their demands on innovation.

- This shift in attention also extends to what constitutes innovation in the first place. Social and organisational innovations are not only complementary to technological innovation but equally important novelties in their own right. Often, they cannot be dissociated from each other and require a stronger role and thus empowerment of people (OECD 2010). R&D is just one contribution to innovation. This is particularly obvious in the service sector where innovation takes place despite the lack of explicit and dedicated R&D.

- Finally, it is also increasingly recognised that there is no single innovation model that fits the requirements of all fields of innovation. Greater diversity in research and innovation patterns can be observed, as reflected in the greater attention paid to sectoral and thematic specificities of innovation.

Future Requirements for Innovation Policy and Its Governance

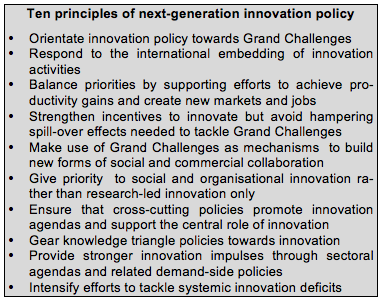

A total of sixteen principles or “commandments” of future innovation policy and its governance were formulated in the context of the workshop. They apply to the European as well as at member states level:

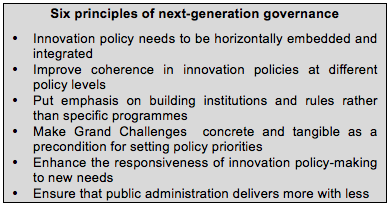

In addition to these principles of innovation policy, six principles were formulated that should guide the future governance of innovation policy in Europe.

A Success Scenario Framework for Future Innovation Policy in Europe

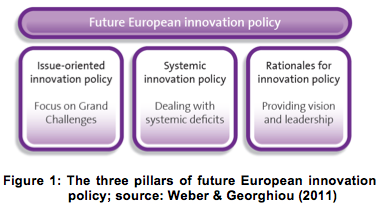

The competencies of the EU in matters of innovation policy are limited. However, to make the most effective use of the specific advantages that these limitations imply, the participants of the workshop suggested a framework that builds on three major pillars of European innovation policy (see Figure 1 in the next column).

Pillar 1: Issue-oriented innovation policy: Focus on Grand Challenges

In line with the Innovation Union flagship initiative, a reframing of innovation policy as a means not only of enhancing competitiveness is recommended but also for addressing Grand Challenges. In order to achieve this, the policy instruments available to the EC are limited, but it could nevertheless spearhead the principle of recognizing and using all forms of innovation – technological, social, organisational and institutional – as equally important means of tackling societal challenges. This principle also implies that simply combining research and innovation policy is not enough because it would imply a restriction to research-led innovation and thus ignore the importance of the other dimensions of innovation needed to meet such challenges. Instead, the EC could strive to inject innovation objectives into its sectoral and cross-cutting policies: a range of powerful demand-side policy instruments could be used to support innovation for tackling Grand Challenges.

A number of concrete examples of first pillar policy initiatives were also suggested, such as

- going beyond an integration of research and innovation policy and considering the integration of innovation agendas into sectoral policies, or

- making innovation-friendliness a standard criterion for defining “good practice” regulations in sectoral policies.

Pillar 2: Systemic innovation policy: dealing with systemic deficits

Grand Challenges should not become the sole concern of European innovation policy. There are a number of cross-cutting problems and systemic deficits that need to be addressed through a targeted innovation policy at the European level, including the Community patent, the realisation of an internal market for innovation-oriented procurement, state aid rules, or the improvement of framework conditions for enabling the fast growth of high-tech companies. If indeed innovation becomes a major concern of sectoral and cross-cutting policies, systemic innovation policy initiatives are likely to receive widespread support in related policy areas as they will be recognised as crucial drivers for realising their mission of tackling Grand Challenges through innovation.

Examples of second pillar policy initiatives comprise

- adjusting state aid rules and other elements of competition policy in order to remove inherent barriers to innovation and

- revisiting public procurement practices and regulations to enable the full exploitation of their innovation-enhancing potential across borders and in the context of Structural Funds.

Pillar 3: Orientation and rationales for innovation policy in Europe: providing vision and leadership for innovation to become a horizontal concern in a multi-level policy context

The political competencies of the EU may be limited, but this apparent weakness offers the opportunity to fulfil the role of intellectual leader in the innovation policy debate in Europe. By identifying deficits, developing visions and formulating rationales for innovation policy, the EU can provide orientation and common reference points for all levels and areas of policy. This has already happened in the past; the momentum generated by the European Research Area concept is a clear example of leadership, in spite of limited formal competencies. Intellectual leadership has the potential of projecting strong messages, which can be communicated to the highest levels of decision-making as well as to the public. In this way, innovation can be assigned the highest priority on the policy agenda. The notion of Grand Challenges is very helpful in this regard because it has the potential for connecting seemingly abstract notions of innovation policy with the deepest concerns of citizens. However, in order to be convincing, European institutions must lead by example, i.e. the concept of innovation needs to be much more embedded in the actual operations of public administrations. An “entrepreneurial innovation policy”, for instance, requires that risk-taking and collaborative modes of policy-making are internalised in the EC services as a starting point if member states are to follow the lead.

Policy initiatives that are in line with Pillar 3 are, for instance

- establishing a culture of co-development in public administration to enable effective procurement procedures, including the fostering of training and information exchange about experiences and good practices in co-development and

- providing incentives to encourage experimenting and risk-taking in public administration at the European level, for instance, by alleviating provisions on personal financial liability for EC staff and by supporting a risk-tolerant and trust-based approach to managing innovation.

Keys to Future Governance of European Innovation Policy

By its very nature, the results of the exercise were very much geared towards providing policy insights, both with regard to substantive policies and the governance of innovation policy. Key questions of governance will need to be tackled in the coming years if the three pillars model is to be realized. At the workshop, some ten governance questions were formulated alongside with some first tentative inroads for dealing with them, but much more effort is needed to realize a significant change in European innovation policy governance:

- How can innovation become a key concern across all sectoral and cross-cutting policies?

- How can shared future visions be established that have the necessary weight to be meaningful for decision-making?

- How can Grand Challenges be concretized to provide operational orientations that help ensure coherence and alignment across policy areas?

- How can horizontal coherence of policy development and design be ensured?

- How can a distributed model for policy implementation be defined?

- How can coherence in innovation policy be achieved in a multi-level governance setting?

- How can coherence with stakeholder opinions, interests and decisions be achieved?

- How the EC can deliver a range of outcomes with less resources?

- How can transparent and rational communication be ensured?

- How policy learning based on local experiences with new forms of innovation be improved?

| Authors: | Matthias Weber matthias.weber@ait.ac.at

Luke Georghiou Luke.georghiou@mbs.ac.uk |

|||||||

| Sponsors: | EU Commission | |||||||

| Type: | EU-level single issue foresight exercise | |||||||

| Organizer: | FP7 Farhorizon Project Coordinator: UNIMAN, Luke Georghiou | |||||||

| Duration: | Sept 08-Dec10 | Budget: | N/A | Time Horizon: | 2020 | Date of Brief: | Feb 2011 | |

Download EFP Brief No. 182_European Innovation Policy

Sources and References

European Commission (2010): Europe 2020 Flagship Initiative Innovation Union, Communication from the European Commission, COM (2010) 546 final, Brussels

OECD (2010): The OECD Innovation Strategy: Getting a Headstart on Tomorrow, Paris

Weber, M., Georghiou, L. (2011): Dynamising Innovation Policy. Giving innovation a central role in European policy, Synthesis Report of a Foresight workshop organised as part of the FP 7 Blue Skies Project FarHorizon

For further information on the FarHorizon project see http://farhorizon.portals.mbs.ac.uk/